Your Cart is Empty

People imagine Central Asia as desert but there are also fertile valleys, cotton fields and spectacular mountain ranges. Its republics- Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan- cover an area ten times the size of Britain, stretching from the Caspian Sea in the west to the Chinese border in the east. For many years their music filtered out as a peripheral and exotic sound from the Soviet Union, but with their independence the six Muslim states are revealing distinct musical treasures.

The Central Asian Republics share a common historical and cultural background in the Islamic faith and- except for Tajikistan – their Turkic roots. The area is a meeting point between Turkic and Iranian people, culture and traditions.

The most elevated musical tradition of Central Asia is the Shashmaqam- the ‘Six Maqams’ of Uzbek and Tajik music. As a courtly music of the upper classes, it earned disapproval from the communists and was forbidden for almost a decade as it didn’t ‘represent the needs of the people’. In an attempt to make it more politically acceptable, texts were rewritten by popular communist poets.

A similar thing happened with the venerable Central Asian art of the improvising bards. The bakshy and akyn minstrels sang of the heroic labour and socialist ideas.

The Soviet ideal of Central Asian musical life was that of socialist Beethovens, Tchaikovskys and Musorgskys composing concert works based on the people’s folk music, while the real traditions of one of the world’s great oral musical cultures were portrayed as feudal and archaic.

People from Azerbaijan are Turkic speaking and of Central Asian origin. There is much influence from Iran there and strong historical connections with Persia. The most celebrated musical tradition of Azerbaijan is the refined classical mugam. This is much freer, lighter and emotional form than the Shashmaqam of Central Asia. Mugams refers to the modes in which the music is played and to the genre itself. The most celebrated texts, usually divine love, come from Sufi poets. Each of the suites is named after its principal mode ormugam in which it will begin and end. The instrumental ensemble is usually a trio of tar (lute), kemanche (spike fiddle) and daf (frame drum) - similar to that found in Persian music. The santur (hammer dulcimer) and nay (flute) commonly heard in Iranian ensembles and Arabic and Turkish oud (lute) are not usually used by the Azeris.

The King of mugam singers is Alim Qasimov who is celebrated for the emotional power of his voice and his expressive vocal ornamentations.

In the late sixteenth century, Bukhara finally became an Emirate capital, and a cultured, cosmopolitan city with flourishing trade routes fuelling its bazaars. It was from this court the Shashmaqam , the most elevated musical form of Uzbek and Tajik culture, derived. It began as a royal music- in a world most familiar from miniature paintings- of princesses and pavilions, with women musicians, sitting on floors, playing on instruments like the gidjak (spike fiddle) dutar (long-necked plucked lute) and doira (circular frame drum).

A Shashmaqam ensemble of the classical period might contain two tanburs, a dutar, a gidjak and doira plus two or three singers. Today’s ensembles are much the same. The pre-eminent Uzbek performer ofShashmaqam and Uzbek classical traditions is Munadjat Yulchieva. The leading performer of instrumental maqam music is Turgun Alimatov- a master-performer on the dutar, tanbur and sato (a bowed tanbur) an instrument he himself revived.

The main focus for Uzbek (and all of Central Asian) music is the toi – the rites of life and celebrations. Uzbeks have a beshik-toi (celebrated forty days after the birth of a baby), a sunnat-toi (for initiation into Islam) and the marriage toi and so on. A toi is also an important musical academy. It’s where musicians gain their experience of practical music-making. In contemporary popular music the big name is that of Yulduz Usmanova who is successfully modernising Uzbek traditional music and bringing it to a much wider audience.

The musical links with neighbouring Uzbekistan are strong and they share their musical shashmaqam repertoire. The Tajiks use Persian-derived texts, but the instrumental music is just the same as in Uzbekistan. While the music of the plains and river valleys is closely related to that of the Uzbeks, in the mountainous south of Tajikistan there’s another more popular style known as falak, which literally means ‘celestial dome’, performed at weddings and other ceremonies and at the nowruz spring festival. The leading performer is conservatoire trained Davlatmand Kholov. He is a fine singer and particularly a good instrumentalist on the gudjat and the sutar and setar.In the Pamir mountain region of Badakshan there is also a rich variety of music including folk poetry and Persian influenced ghazals (poetry form) and praise songs.

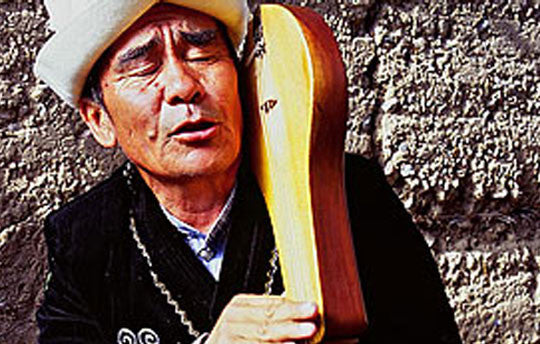

There is a clear division between the nomadic and the settled people of Central Asia and this is reflected in the kind of music performed. The city populations are primarily made up of Uzbeks and Tajiks and their music belongs to the urban classical and professional tradition. Kazakhs, Turkmen and Kyrgyz, however, are of nomadic origin and their music follows the rural or folk traditions which have a closer connection to a pre-Islamic animist and shamanist culture. Related to this is the art of the bard or bakshy - another branch of the widespread Turkic asik tradition. In these societies which are still close to their nomadic origins, the bakshy is also a shaman-acting as healer, magician and moraliser. All three countries have traditions of sung epics performed by the bakshy. The group Ashkhabad from Turkmenistan has recorded its own particular brand of wedding music. Their music draws on the song-epics and folk traditions and is adapted somewhat for western audiences and through their own Western classical training.